Topic: CRS Versions

Larry Holcomb believes Lynn Rohrbough’s Cooperative Recreation Service (CRS) began publishing custom songbooks in 1940. [1] The first may have been a collection for the American Country Life Association. [2] One suspects it was commissioned by someone at Ohio State University or Ohio Wesleyan University who was active in the organization. [3]

Custom songbooks were not invented by Rohrbough, although there are aspects he may have rediscovered. The first seems to have been produced by Carl Edward Zander [4] and Wes Klusmann for Boy Scouts in California. The exact history does not emerge until they copyrighted a book in 1938 for the YMCA. [5]

The one I own is the “28th printing” from 1938. [6] The format is the same as that used by CRS in the 1930s: 3 6/16" wide by 6 7/16" long. [7] This booklet’s cover is thin cardboard while the pages are heavy stock. It is held together with two staples.

The Boy Scouts of America was organized in 1910 by a committee that hoped to merge the programs of Ernest Thompson Seton and Daniel Beard with the British program of Robert Baden-Powell. Since none of the men involved had an interest in administration, the group hired James Edward West as manger. He quickly dispatched Seton and Beard, and treated the organization as a business. [8]

A number of Scout councils had organized camps on their own that combined Scouting programs with those of private boys’ camps in New England. In 1918, West reduced costs when he transferred the burden of troop organization over to local churches. In 1926, he replaced existing camp programs with troop camping. Councils provided safe sites, and local troop leaders provided manpower. [9]

Zander’s name first appears as a council executive and camp director in 1924 and 1925; [10] after that troop camping prevailed. Klusmann’s name first appears when he was associated with the Woodcraft League of America in 1928. [11] That group was sponsored by Seton. [12]

Local councils circumvented West’s limited camping programs in small ways. Zander and Klusmann did not copyright their songbooks for the Boy Scouts. Instead, they seem to have created a private business, Songs ’n’ Things, in Berkeley. Both were the sons of entrepreneurs. Klusmann’s father sold pharmaceutical supplies, [13] while Zander’s was “a musician who played, taught, and had a music store.” [14]

According to historians for the Crescent Bay BSA District, the first book was called Camp Songs for Boy Scouts. It contained fifty songs and “circulated widely throughout the scout camps of Southern California and beyond.” [15]

Camping and youth group organizations were strong in California and other groups asked for copies. That led the two men to issue Camp Songs: Popular Edition, which they modified for different markets by including songs specific to each group.

The two Boy Scout field executives modified the “21st printing” by substituting Camp Josepho’s name in place of “popular edition” and added a four-page insert in the middle that had no page numbers. Later, they altered the “23rd printing” by adding an eight-page section of Josepho’s songs that were numbered in sequence. [16]

My 1938 copy of Camp Songs does not contain music, only the lyrics with notes on the tunes.

In 1939, Zander and Klusmann introduced a second collection, Camp Songs ’n’ Things [17] that does have music. It also includes some stunts.

Printing did not mean print run, but version of the master songbook. The date refers to the copyright date of the title, not the date of the publication.

As you can see, the type is in two fonts. The constant information is darker than the text that changes. They may well have had one plate where they made the substitutions. Crescent Bay says their “21st printing” was from 1942 and their “23rd printing” from 1945.

My “1938” copy of Camp Songs: Popular Edition contains “Walking at Night” with a credit to the National Recreation Association. The first publication was 1940 in Augustus Zanzig’s Singing America. [18] As mentioned in the post for 26 September 2021, Zanzig was traveling around the country collecting songs, and may well have introduced this in California before he issued his songbook. [19]

Zander and Klusmann’s use of dates and version numbers makes it difficult to know exactly when the two men introduced particular songs. The only time limit would be 1943, when Klusmann moved to New York to work in the national BSA office, [20] although Crescent Lake indicates Zander must have continued the business a few years longer. His family remembers “him in his den packing up and shipping out Songs 'N Things books” years after he was “out of Scouting.” [21]

Graphics

1. Camp Songs, front cover.

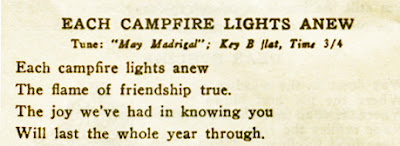

2. “Each Campfire Lights Anew.” Camp Songs, page 50.

3. “Each Campfire Lights Anew.” Camp Songs ’n’ Things, page 94.

4. Camp Songs, inside back cover.

End Notes

Zander and Klusmann are mentioned in the posts for 5 December 2021, 13 March 2022, and 20 March 2022.

1. Larry Nial Holcomb. “A History of the Cooperative Recreation Service.” PhD dissertation. University of Michigan, 1972. 102. Reconstructing this phase of CRS’s history is difficult for several reasons. Rohrbough’s memory cannot always be trusted. Business records before 1960 had been destroyed by the time Holcomb was working with Rohrbough. [23] Few songbooks carry dates of publication, and often that information is not reliable. In their place, one must compare songbooks looking for internal evidence. Rohrbough did not keep copies of everything he produced, and Holcomb amassed his collection from rummaging through the storeroom and talking to friends. [24] I have been buying copies on-line, and that is limited to those that survived sixty or seventy years. When my information differs from his, I assume his usually is correct and my source is later than his.

2. American Country Life Association. Songs. 1940 according to Holcomb. 104.

3. The American Country Life Association was founded in 1919. [25] Paul Vogt of Ohio State University [26] and Bruce Melvin of Ohio Wesleyan University in Delaware, Ohio, [32] were early supporters of the group. Both had left the state by the mid-1920s, but others remained active. OSU hosted the 1935 national conference. [36] I have not found the names of anyone active in the group in the 1940s in Ohio.

4. When he was publishing songbooks, Zander used the name Carl. Later, he used Edward. I will use his full name to make clear he is the person being discussed.

5. Carl E. Zander and Wes H. Klusmann. Camp Songs: Popular Edition. Los Angeles: 4 May 1938; edition for Y. M. C. A. Item AA 269978 in United States Copyright Office. Catalog of Copyright Entries. Part 1. Number 7, 1938. 785.

6. Carl E. Zander and Wes H. Klusmann. Camp Songs: Popular Edition. Berkeley, California: Songs ’n’ Things, copyright 1938, 28th printing.

7. The post for 12 December 2021 has a photograph of the CRS Handy II cover from 1930.

8. Patricia Averill. Camp Songs, Folk Songs. Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris, 2014. 367–368.

9. Averill. 368.

10. Alan O’Connor, Gerry Albright, Cliff Curtice, Irene Fujimoto, Frank Glick, Howard Herlihy, John Nopel, Bill Soncrant, Janette Soncrant, and George Williams. “History of the Golden Empire Council: Boy Scouts of America.” Sacramento, California: Golden Empire BSA Council, 1996. 33.

11. Item. Eagle Rock Sentinel, Los Angeles, California, 20:6:24 February 1928.

12. Averill. 145.

13. The National Corporation Reporter, 8:130:1894, lists The William H. Klusmann [37] Company as a manufacturer and dealer in “essential oils, juices of plants and vegetables, drugs.”

14. BG. “Carl Edward Zander Sr.” Find a Grave website, 8 February 2021.

15. Crescent Bay Historical Project. “Camp Josepho - Song Books.” Crescent Bay District, West Los Angeles BSA Council website, Jeff Morley webmaster.

16. Crescent Bay Council.

17. My copy is Carl E. Zander and Wes H. Klusmann. Camp Songs ’n’ Things. Berkeley, California: Songs ’n’ Things, copyrighted 1939, ninth printing. I could not verify the copyright status from the Library of Congress catalogs available on the internet. Except for the use of music, it has the same format as Camp Songs.

18. Augustus D. Zanzig. Singing America. Boston: C. C. Birchard and Company, 1940.

19. The post for 5 December 2021 provides evidence that Zanzig was spreading songs before he published Singing America.

21. “Regional Meeting.” Oakland Tribune, Oakland, California, 14 March 1943. 23. Among those attending was “Wes H. Klusmann, National director of camping.”

22. Carl Edward Zander’s family. Email, 3 November 2021.

23. Holcomb. 104.

24. Holcomb. 104. “Most of those that the author found were located in the shelves of surplus and reference books at the CRS headquarters--an enormous but incomplete source. Others were found in the private libraries of many longtime friends of the Rohrboughs. Titles, dates, and purchasing groups of some additional custom songbooks were discovered in various advertising flyers of the CRS.”

25. Merwin Swanson. “The ‘Country Life Movement’ and the American Churches.” Church History 46:358–373:1977. 369.

26. Vogt published his text on Rural Sociology in 1918 [27] while he was at OSU. [28] He took a position with the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1916 promoting improvements in rural churches. [29] He left that job in 1926 [30] and was living in Philadelphia in 1923. [31]

27. Paul Leroy Vogt. Introduction to Rural Sociology. New York: Appleton, 1918.

28. “Paul Leroy Vogt.” Everybody Wiki website.

29. Swanson. 367.

30. Swanson. 371.

31. American Country Life Association. Proceedings, 1923 conference. 201.

32. Melvin was on the association’s committee on teaching of rural sociology in 1923 while at Ohio Wesleyan. [33] In 1926, he was at Cornell. [34] In 1938, he was promoting on recreation programs as ways to prevent delinquency in rural areas. [35]

33. American Country Life Association, 1923. 200.

34. Bruce L. Melvin. “Methods of Social Research.” Listed in “Preliminary Program of the Twenty-First Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Society” published by American Journal of Sociology 32:471–476:1926. 472.

35. Bruce Lee Melvin and Elna Nielsen Smith. Rural Youth: Their Situation and Prospects. Washington DC: Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1938. 83.

36. Fred R. Yoder. Review of “Country Life Programs.” Rural Sociology 1:530:1936.

37. “Wesley Herman Klusmann.” Ancestry website. It blocks information on his father, William H. Klusmann.